When I was a child

my heroes were immortal.

Now, they’re mostly gone.

Notes:

If you had talked to me when I was 9 or 10 years old, I would have told you I was sure I was going to be a baseball player when I grew up. Many a long summer day was spent playing sandlot games in the vacant lot behind Fitzgibbon Memorial Hospital in what was universally known as “The Hospital Yard.”

No adult supervised. A wide range of ages played. There was Tommy Fox, with his wicked left-handed batting. Big Wayne Halsey, an older kid, who once hit a ball over the huge trees at the far end of the lot. Steve Cunningham, God rest his soul, played, and so did the Mounts brothers, Paul and Steve. And many more long forgotten.

Somehow, we just figured it out, negotiating disputes and triangulating our way to make games fair. When we didn’t have enough players to form respectable teams, we played games designed for smaller numbers like “Work-Up,” or “Five Hundred.” These games might not have been as exciting as full-fledged baseball, but they enabled us to keep playing long after most of the other kids had to go home.

So we played until we wore ourselves out, until darkness fell, or until our mothers hollered for us to come in for supper.

To be sure, there was an organized baseball league out at the municipal park, but it was a pretty low-key affair, with maybe one or two games a week. Not nearly enough to satisfy.

In between these baseball games, I would hang out with my buddy Royce Kincaid and play 2-man whiffle ball. We had devised elaborate rules that enabled us to play entire games against each other all by ourselves. We would each pick one of our favorite professional teams, and pretend to be each of the starting players. We were such fanatics that — even though neither of were ambidextrous — we would bat right-handed if the player batted right, and bat left-handed if the player batted left.

We were pretty evenly matched and the competition was fierce. We could argue close calls, and learned how to give and take for the sake of the game. Neither of us wanted to push any argument to the point of risking the continuation of play.

We knew our information about the professional players because were also fanatical baseball card collectors. For a stretch that spanned about 3 or 4 years, we devoted a very large percentage of our meager kid income to buying baseball cards at 5 cents a pack. Back then, the cards came with a pink slab of bubblegum dusted with white powered sugar.

We didn’t really care about the gum. We wanted the cards. We would beg our parents for cards on every trip to the A&P, IGA, or MFA grocery store. We would haunt the small neighborhood grocery stores that served our little town back in the days before convenience stores looking for good cards.

We figured out that the Topps Baseball Card Company would release the cards in flights over the course of a baseball season. We would start the year with every pack full of unique new treasures. But soon we would start finding our purchased packs full of cards we already had — “doubles,” we called them.

We would still cautiously buy packs here and there, sometimes prying the packs open to sneak a peak inside to increase our chances of getting a card we didn’t already have.

Then, when we discovered that a new series had been released, we rush out with our nickels in our hands ready to splurge again. I remember riding my bike all the way to the west end of town to buy “fresh” cards at a little store that had gotten them before anywhere else.

We would get together with other guys and trade cards, and show off our collections. But mostly we looked at the cards and studied them. I arranged them by team, and position. I studied the statistics on the back and memorized the trivia about each player. When the St. Louis Cardinals or Kansas City A’s were on the radio, I would pull out the cards of each team and follow along as each player batted.

Back in those days, the Cardinals came in loud and strong on KMOX, and the games were called by Jack Buck and Harry Caray before Harry defected to Chicago.

I got to taste both victory and defeat. The Cards were in one of their many periods of greatness. The A’s were pitiful losers, more of a backwater club that seemed to always sell its most promising players to the hated N.Y. Yankees just before they hit their prime.

In those days the A’s were owned by impresario Charlie Finley, who pushed the boundaries of good taste and good sense. He introduced garish the garish Kelly Green and Gold uniforms, and brought a mule named Charlie O into the stadium. When Finley moved the team to Oakland in 1968, I washed my hands of them. The fact that they soon started winning in their new city only made me hate them more.

But, did I ever have some great cards! Bob Gibson. Mickey Mantle. Hank Aaron. Roberto Clemente. Sandy Koufax. Don Drysdale. Ernie Banks. Yogi Berra. Willie Mays. Tim McCarver. All of the greats from the early 60s.

I was sure someday my face would be on one of those cards.

But life has a way of going in unanticipated directions. I grew up and developed more of an interest in girls than baseball.

In just a few years the cardboard box of baseball cards was shoved back under my bed and largely forgotten.

It was not until I had kids of my own and came back to visit my parents that I inquired about the baseball cards. They had disappeared, and my mother, who had guarded my old room like a museum shine, had gradually lost her memory.

I had pretty much given up ever seeing the old keepsakes again, when my father remembered that my mother had stashed some of my items in an old dresser drawer in her bedroom.

Sure enough, behind some old blouses I found a small box of baseball cards! They were not the full set. It was my old box of doubles.

But it was like a reunion with old friends. There was Roger Maris and Sandy Koufax. And Duke Snider and Kenny Boyer. There was even an old Jerry Lumpe card. A good player, but never a big star, Jerry was notable at least in our neighborhood because he played for the Kansas City A’s and Freddie Mueschke, the neighbor kid who lived on the corner, claimed to be Jerry Lumpe’s nephew.

We never verified Freddie’s story, but he got a lot of mileage from that claim to fame.

(I was gratified to learn that Lumpe has his own entry in Wikipedia. He even managed to have such a good season in 1964 that he was named to the American League All Star Team. That happened the year right after he was traded from the A’s, of course.)

A lot of my best cards were missing. No Mickey Mantles or Hank Aarons. But it was still like finding a treasure trove nonetheless.

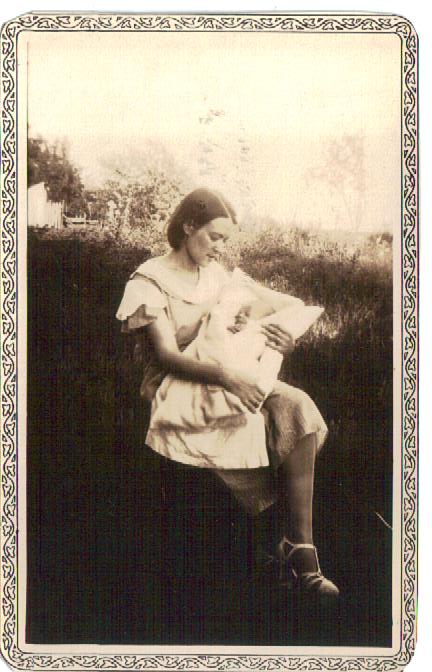

Mom had reached through the years and through her senility to bless her little boy with one last small gift. By this time she was lying in a nursing home without a memory. But her gift to me had restored a whole storehouse of memories.