He Knew the Worth of Tools

He was a man who knew the worth of tools.

How having just the right one for the job

Was worth a lot, but clearly not as much

As knowing what to do with ones you had,

And what to do with tools he surely knew.

When just a boy on a Missouri farm,

He started hanging round the blacksmith shop

Whenever he could catch a ride to town.

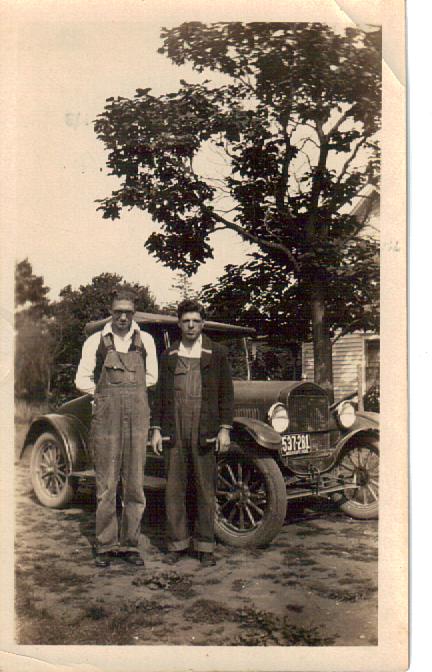

Old Henry Ford’s new-fangled auto car

Had sparked a need for handy fix-it men.

He joined the revolution, then and there,

Brought by the horseless carriage on the land,

And learned mechanics on a Model T.

He mastered use of wrenches and of pliers,

Learned lessons he would use for decades hence.

To make it through the Great Depression’s dearth

He took whatever labor he could find.

He hoed bean rows and stripped bluegrass by hand,

With just the simplest tools to do the job.

His daily wage back then was just a buck,

But any honest work beat none at all.

To earn his daily bread he tilled the soil

Just like his male ancestors all before.

But he saw tools of farming changing too,

With tractors putting horses out of work.

He gambled on a combine harvester

That reaped and threshed and winnowed all at once.

Then hiring out his cutting-edge machine,

He saved enough to buy his own small farm,

And one by one he added to his tools.

In time he sold the farm and moved to town

To try his hand in the commercial world.

Still very much a Ford man in his heart,

He bought a dealership of farm machines—

The boldest speculation of his life.

But business wasn’t really his strong suit,

And when it failed, he carried on with tools.

He built a practice fixing implements —

Hay balers, corn pickers, tractors — all repaired

Right where they’d broken down out in the field.

And farmers round about began to say,

“If Ray can’t make her run she can’t be fixed.”

When he was well past sixty years of age

He got a crazy notion in his head—

He’d always dreamed of having his own shop—

So he measured out the plan in the back yard.

And there he built the thing all by himself

With salvaged lumber gotten almost free.

Of course, it looked just like a barn.

Because, well, that’s only thing that he’d built before.

But he knew well enough the tools required.

Beneath his hammer, nails sunk into boards

With just two strokes, or maybe three.

His singing handsaw made the sawdust fly.

His level, plane and plumb line kept all true.

Out of a worthless demolition pile

He fashioned form where there was none before.

His barn still stands though many years have passed.

With paint and care could stand for many more.

It needs someone with tools to care again.

And when his wife of more than fifty years

Grew absent minded and began to fail,

He looked in vain for tools to fix her with.

Installed a cook-stove, gas-line, shut-off valve

When she began to start forgetting things,

Like if she’d turned the burners on or off.

Nowhere on all his cluttered workshop shelves

Was there a tool to fix her slipping mind.

The final years he’d visit every day

Ensuring that she ate her rest home meal.

The only tool of any use a spoon.

In time, the spoon was of no use as well.

My work today requires different tools.

I toil in neither soil nor wood nor stone.

Instead of grease my hands are stained with ink.

I polish common syllables to rhyme.

I calibrate my words to find a song,

Fine tuning—like a carburetor—lines,

To make them run not either rich nor lean,

To purr and roar without the gassy fumes,

Obscuring sense and choking with the smoke.

My father’s tools lie idle on the bench.

The workman will not use them anymore.

With all the craftsmanship I can bestow,

I carry on instead with tools I know.

(2019)

I’ve been reading a lot of Robert Frost this year. He was a modern master of blank verse and all of that exposure is bound to have some influence on me. I can only hope some of the music rubs off on me.

Back in May, I took a stab at blank verse and it seemed to work out okay. So here is another in the same vein.

The workman in this poem is my father. I am living proof that mechanical aptitude is not hereditary.