The Old House Sure is Quiet

The old house sure is quiet since you’ve gone.

Mom can’t get used to cooking just for two.

You won’t believe how much weight we’ve put on.

We’d hoped to get a note by now from you.

These letters now are half a century old,

Confirm I was a most neglectful son.

No matter how I wish the tale retold,

That page is turned. That episode is done.

And so I write this meager note to you,

Dear Father, only parent I have left.

Your fondness for your prodigal issue

Outlives their fondness, who left me bereft.

May you this orphan never leave alone,

May your fire find and melt this heart of stone.

(2018)

NOTES: Reading old letters is not for the faint of heart. I’ve been going through a box that includes the letters my parents wrote to me during my freshman year of college.

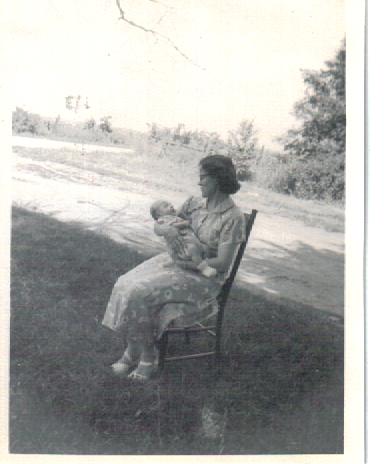

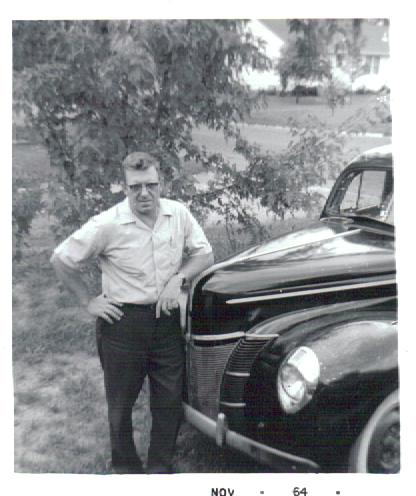

I am older now than they were then, and I am definitely identifying with them in this story. I was the youngest of their children (by a long shot) and they had become empty nesters after having had children in the house for nearly 40 consecutive years. They were pushing 60, still working hard to make ends meet, and now suddenly living by themselves.

They wrote me several times a month, usually on Sunday evenings. They each filled both sides of a full sheet of paper.

The message that comes through, again and again, is: “Please write and let us know how you are doing.”

I have no idea how many times I wrote them back, but from the plaintive tone of their letters, it couldn’t have been very many.

And that figures. I was off on the Big Adventure of my youth. Determined to grow up and become my own person and form my own beliefs. Remember, this was 1970. Maybe not the peak of the counterculture, but you could see it from there.

I recently read an article about the attitudes of college freshmen over the years. The subject being investigated concerned the students’ desire to work towards a good job with security.

The year that scored the absolute lowest was–you guessed it–my year, 1970. And I was pretty typical. Despite my long-suffering father’s most excellent advice to “study something practical,” I thought my purpose was to discover Truth, Beauty, and Love. I remember heading off to school with the express intention to NOT study anything practical that would lead to a regular job. (And I certainly succeeded at that! When I finally graduated five years later with a B.A. in philosophy and classics, I was fully qualified to be a fry cook, and that was about it.)

It took several years and going back to school before I developed any marketable skills.

But back to my folks.

They were such faithful correspondents. They diligently reported news they thought I would be interested in. Like who they ran into up on the square … which of my old schoolmates were married and having babies … news from the high school. Who was crowned homecoming queen–that was big news. And they faithfully reported the high school football scores each week.

I didn’t realize how much they had enjoyed going to my games, and although I was no longer playing, they would occasionally take in a game, or at least listen on the radio or read the local newspaper, and they would report the scores to me.

But of course, I was pretty much over all that.

Those days are sort of hazy for me, but I know I was finally off on my own and trying out everything I had refrained from doing in high school for fear of getting kicked off the football team.

My folks were lonely, to be sure. But beyond that, if I may project a little, they were being faced with their own mortality, and their own sense of purpose and meaning.

The more well-off set of their generation cashed out of their suburban homes and headed for Florida or Arizona and retired to a life of relative leisure. And who could blame them? They had put their lives on hold to save the world during WWII, then they had come back and built the greatest economy the world had ever seen.

But my parents weren’t quite in that class. They had raised 4 boys, helped take care of a handful of grandkids, and now that I was gone, they weren’t sure what to do next. Except they had to keep on baking pies and driving busses and fixing tractors. Retirement really wasn’t an option. Meanwhile, the whole society, as reported in TIME magazine, seemed to be turning upside down all around them.

And then, when their prodigal son finally deigned to write from college, he babbled about crazy things. I was studying impractical subjects. I was planning to go to Mississippi to register voters. I was learning yoga and wanting to have serious conversations about serious subjects.

Neither of my parents had been able to get much of a formal education, yet they were patient with their insufferable son. My mother didn’t even get to go to high school because her mother had died during the influenza epidemic early in the last century, leaving her as the eldest daughter (although she was just barely a teenager) to run the household and raise all her younger siblings. My father came of age smack in the middle of the Great Depression, and was forced to drop out of high school to start earning a living, working as a farmhand for a dollar a day.

We had a bit of a generation gap.

And yet, my parents’ hobbies belied their lack of education. My mother read poetry. From an early age, she would recite the verses she loved to me from her beloved volume of the most loved poems of the American people.

She read the American classics of the time: Wordsworth, Emerson, Eugene Field, and even that new fellow, Frost. Some of my earliest memories are of her reading to me from “The Duel” (aka “The Gingham Dog and the Calico Cat,”) “Lil’ Boy Blue,” and “Hiawatha.”

She would dutifully clip poems out of the Capper’s Weekly and stuff them into the letter she sent to me each week.

My father, meanwhile, was a serious student of the Bible and ancient history. He would order Bible commentaries and translations of ancient writers such as Josephus and Philo to supplement his Bible reading.

Looking back with the perspective of time, I see a couple of very intelligent people who had their potential abbreviated by circumstance. I also see I was a very lucky kid who was in grave danger of pissing away great opportunity.

And most of all I see a clueless teenager who had no idea of the hopes and fears and heartaches of his parents.

Many years later, when my own children played their last high school games, graduated and went off to college … when they were thousands of miles away in another country and didn’t check in as often as I would have liked … only then did I have a glimpse of what must have been running through my own parents’ hearts so many years ago.