Father, when you spoke

I believed you, for you spoke

with authority.

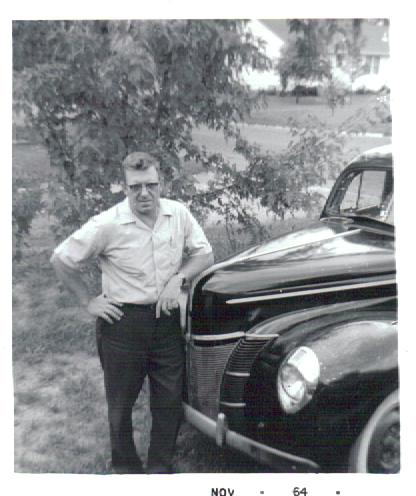

NOTES: In many ways, my dad was a simple man. Farmer. Mechanic. Forced to drop out of high school to work during the Great Depression, he never had the opportunity go back to school to pick up his education again.

He never travelled to Europe or learned a foreign language. He never made a lot of money, or tasted the luxuries of life.

But he knew what he thought and what he believed. And when he talked about his beliefs, his strength of conviction came through his voice.

Often he was expressing his belief in the products of the Ford Motor Company. He was a confirmed Ford man. He claimed he had seen the insides of enough cars and tractors to know how each one held up, and which ones were made out of cheap materials.

He would just utter a phrase like, “The Ford Model T …” and let it hang there and resonate in the air. He said it with such reverence that those who heard it just knew that the Ford Model T had not only been a great automobile, but a miraculous product of a genius.

He could inspire similar feelings of reverence with exclamations like, “President Abraham Lincoln,” or “Old Thomas Edison.” You just knew these were great men.

We didn’t have pastors or full-time clergy in our tiny little Church of Christ congregation. The leadership was handled by laymen like himself. When he would stand up on Sunday mornings to “wait on the communion table,” he would recite the words by heart from the King James Version of Paul’s first letter to the Corinthians:

“That the Lord Jesus, on the night he was betrayed took bread, And when he had given thanks, he brake it, and said, Take it, eat: this is my body which is broken for you. This do in remembrance of me.”

Hearing him say it, you had no doubt that this was just the way it had happened.

Perhaps the most convincing and poignant expression of his conviction came many years later, as his wife lay in a nursing home, long lost to dementia. “Your mother,” he said, “was the best. I never met another women like your mother. Never.”

And you just knew it was true.