Seems fitting somehow …

cold day in San Francisco,

reading Kerouac.

Seems fitting somehow …

cold day in San Francisco,

reading Kerouac.

Carmel-by-the-Sea,

so much beauty and money

in one single place.

Dear upperclassmen,

we idolized you so much,

you were like heroes.

Then, that class trip fiasco,

And class trips were abolished.

NOTES: The class ahead of us in high school was impressive. It included some very smart and talented people who challenged and inspired us underclassmen.

Counted among its members were some of the best athletes, actors, debaters, musicians and scholars ever to come out of our little Missouri town of Marshall. When they went away to college in the fall of 1969, they returned on their breaks with fascinating stories of life at their campuses.

I paid close attention to their testimonials, and followed a couple of them when it came time to make my own college choice.

The class of 1969 certainly went out with a bang. Our high school had long had a tradition of the senior class trip, which involved a long trek to some exotic destination far enough away to make getting there grueling and sleep-deprived.

That year the seniors made the long bus ride to Six Flags Over Texas. But during the course of that journey, something happened.

The stories we heard were somewhat hushed and confusing, but whatever happened was so serious that school officials cancelled senior trips forevermore.

The next year, there was not even a discussion about our own class taking a senior trip. Not. A. Chance.

The Class of ’69 was already notable in that it had voted to abolish the venerable tradition of selecting the most popular and respected girl to preside over Achievement Night as Miss Fair Marshall.

Now, our heroes had managed to put the kibosh on another tradition. In a way it enhanced the reputation of the Class of ’69 even further. In addition to all their other superlatives, they had also become the Biggest Screw-Ups.

I’m hoping some of my old schoolmates from the Class of ’69 might finally come forward with the true story of what transpired on that notorious trip. Why don’t you just come clean? Confession is good for the soul and the statute of limitations on your crimes certainly has expired.

Some members of my own class are still a bit aggrieved that we didn’t get to have our senior trip because of you.

It would be good to be able to put the scurrilous rumors to rest, and to finally forgive and forget.

STYLE NOTE: Like haiku, the tanka is a traditional Japanese short poem form with a prescribed number of syllables. The pattern is 5-7-5-7-7.

Unattainable,

cheerleaders stirred crowds and our

imaginations

NOTES: Here’s another invaluable photograph from my friend, Susumu. This must have been taken in the fall of 1968, amidst an exciting small town high school football season.

It most certainly was an away game. The home games of the Marshall High School Owls were played at Missouri Valley College’s Gregg-Mitchell Field, and this setting does not look familiar. I’m guessing it might have been the away game that year at the home field of our most hated rival, the Excelsior Springs Tigers.

Marshall had been playing second fiddle to the Tigers for several years, just unable to put together enough power to overcome dislodge them from the top of the Missouri River Valley Conference.

The year before, we had endured a humiliating defeat as the Tigers came into our stadium and beat us on a frigid night in Marshall. Those old aluminum benches had never felt so cold.

This year turned out much better. Coach Cecil Naylor had us worked into such a frenzy that we could have taken on a band of Viking berserkers. We travelled into the Tigers’ home turf, took care of business, and vanquished them 20 to 0.

But I digress.

The topic is cheerleaders. What is with their mystique? And why couldn’t they get a date with their own classmates?

I could be misremembering, but it seemed that very few cheerleaders ever dated guys in their own class. Older guys might work up the confidence to “date down” with a cheerleader from lower grade. But mating between cheerleaders and a classmate was scare and rare.

One of life’s great mysteries. The Cheerleader Paradox.

Mysterious even when you factor in the fact that in our little town, many of us had attended school together since first grade, and the rest of us had been together in the same building since 7th grade.

The long history and close familiarity meant that most of your classmates were like family. That contributed to sense that the cute girl in chemistry class seemed more like your sister or your cousin than girlfriend material.

I mean, you’d grown up together! You’d seen each other on good days and bad days. Good hair days and bad. You’d fought on the playground in grade school, and competed for teachers’ attention. Not much mystery left.

But even that doesn’t explain the Cheerleader Paradox.

Dr. Freud, call your office. I’m open to hypotheses.

Old streets remind me

I did not know compassion

when I walked them then.

NOTES: I have come into possession of a treasure trove of photos from the late 1960s taken by an old schoolmate, Susumu. He was our Japanese foreign exchange student when I was a junior in high school in 1968 and 1969.

Across the years and across the internet, we reconnected and he sent me the photos he collected during his year in my hometown.

Susumu saw things through his camera lens that I had long forgotten. These are shots I would never have thought to take. Simple street scenes. Iconic buildings long since torn down. Teachers and friends long forgotten.

The gift of these photos is almost indescribable. It is as though I am seeing my hometown again, for the first time. I’m transported back nearly half a century to the place of my childhood, to the places where I lived my formative years.

No fancy Instagram filters are required. These photos already have the faded Kodachrome quality you cannot fake. They come with authentic poignancy.

These photos take me back to my youth. And my heart is filled with questions. What if? If only? Didn’t I realize?

Relax noisy crows,

I mean your babies no harm.

The cat, however …

Such a great view here.

The Cascades are breathtaking.

You’ll need to trust me.

The old crow lingers

on his cold and barren branch

although I draw near.

I Sing Not for Glory

I sing not for glory nor for bread,

Nor for the praise of the credentialed clique.

But for hire more valuable instead,

To touch the honest kindred heart I seek.

I sing for lovers when love is green,

When time stops for a solitary kiss.

When light shines anew as with new eyes seen,

I celebrate your fey and fragile bliss.

I sing for the lonely, lovelorn heart,

When light grows cold and aching will not cease,

When your enchanted world falls all apart,

I offer modest salve to give you peace.

I sing for the pilgrim searching soul

Pursuing the heart’s true cause and treasure.

May heaven’s hound, you hasten to your goal,

And propel you to your proper pleasure.

I sing for the wise who see their end,

And, too, for those who have not yet awoke.

For to a common home we all descend,

With common dirt for all our common cloak.

I sing not for money nor for art,

Nor to amuse curators of our trade.

The simple wages of the simple heart

Will satisfy when my accounts are weighed.

©Bobby Ball 2017

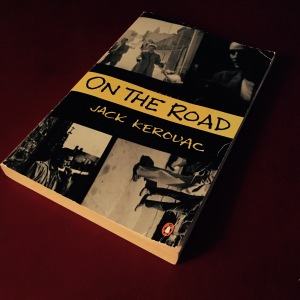

NOTES: Samuel Johnson was a funny guy. If his aphorism is correct, that “no man but a blockhead ever wrote, except for money,” then poets are the biggest blockheads of them all.

A few diligent writers of books and screenplays and advertising copy can manage to make a living scribbling words. But poets need another gig to pay the bills.

Most often, they teach. Gerard Manley Hopkins was a priest and a teacher. Robert Frost famously tried his hand at farming, but he also taught and lectured.

Some poets have conducted quite conventional careers during the day to support their poetry habit at night. Insurance executive Wallace Stevens and physician William Carlos Williams are a couple of well known examples.

Englishman Philip Larkin earned his living as a librarian. American Charles Bukowski was a postal clerk.

Dylan Thomas really couldn’t do much else besides write poems, and so he waged a losing war with poverty until he drank himself to death. He probably would have perished much sooner except for the fact he was able to charm wealthy female admirers into becoming patronesses.

About the only thing I have in common with the aforementioned gentlemen is that while I sometimes commit poetry, I also need another means to make a living.

I started my professional life in the 1970s as an ink-stained wretch of a newspaperman. While chasing deadlines was exhilarating when I was still a young man, there were already storm clouds on the horizon for journalism. Afternoon dailies were going extinct, and cities that had formerly had 2, 3 or more newspapers were seeing them merge or go out of business.

Little did I know that in just a few years, the internet would come along and fatally wound the mainstream media organizations, forcing them to trim their newsrooms and close regional bureaus.

I sensed that there was a disturbing uniformity of political opinion in the newsrooms of my youth. My own political worldview was still evolving, but even back then everybody I worked with seemed to be left-leaning and Reagan-loathing. The lockstep groupthink bothered me.

In my naïve idealism, I thought journalists were supposed to be fiercely objective. I never caucused with any party, and I strove to play my own coverage right down the middle. I’d have coffee with both Democrats and Republicans, and always made sure to pay my own check because I didn’t want to owe anybody anything.

When the owner of one paper tried to pressure me to join the local Rotary Club, I refused because I didn’t want membership to influence my coverage of any organization.

If I had still been a journalist this past year I think my head would have exploded. With news organizations colluding with political campaigns, and sharing debate questions in advance with the favored candidate, it became clear that our creaky old news institutions had jumped the shark.

I would have burned my press card in protest.

I wish I could say I was smart enough to foresee the death of journalism and jump ship intentionally, but it was more random than that. I was about to get married and I needed a job in Minneapolis. The cash-strapped metropolitan dailies weren’t hiring right then, and so I took the first job I could get.

Fortunately I had stumbled my way into direct marketing. That later led me into non-profit fundraising. The bulk of my career since has been helping good causes raise money. Healing the sick, feeding the hungry, caring for widows and orphans, defending the persecuted, visiting those in prison, bringing the good news to those in bondage — that sort of thing.

I began to appreciate what I do a whole lot more when I stopped thinking about it as marketing and started thinking about it as “soul stirring.” When I’m doing it right, I touch the heart to stir people up to good works, and inspire them to be generous.

If you ask me, that’s really just a short step away from poetry. It’s all soul stirring.

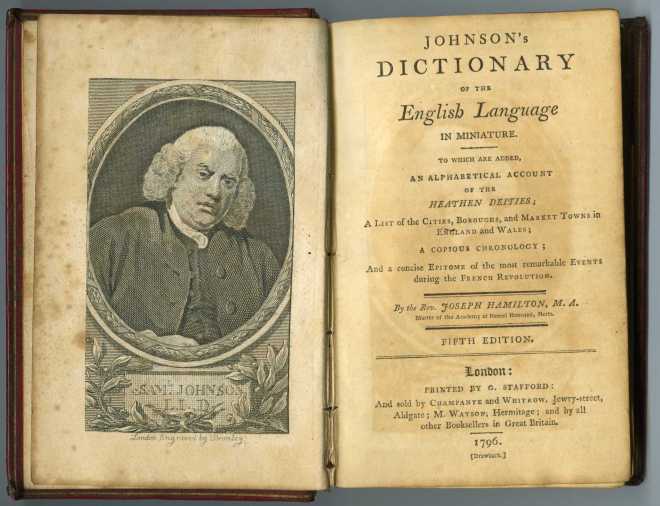

Generations tilled

to eke out a meager life. Now I

scribble in comfort.

Notes: I have to go all the way back to England in the 1600s to find an ancestor who had a desk job. To the best of our family research, my great-great-great (etc.) grandfather was a clergyman back in the old country, who had the poor judgment to raise the ire of the Archbishop of Canterbury.

In those days it didn’t take much to get your head separated from the rest of you. Heretics and troublesome free thinkers could easily meet the same fate.

My forebear wised up in the nick of time and caught one of next boats after the Mayflower to the New World. We are not sure if he stayed in the preaching business in his new surroundings in the Connecticut Colony, but as far as we can tell, all of those who followed him were dirt farmers. (Which probably seemed like a safer line of work back then.)

Several generations later, after my great grandfather Frederick Ball narrowly survived the Civil War, he came back home to find Connecticut getting crowded. So, he headed west for the promise of cheap land and opportunity. He wound up in southern Iowa, got married, acquired some land, and raised a family.

One of his sons was my grandfather, and he, too became a farmer, moving to Missouri to chase opportunity. When my father came along, he showed considerable mechanical aptitude and had hopes of going to school to study engineering. But the Great Depression dashed those dreams. Dad had to drop out of school before he finished high school. To help support the family he became a farmer.

And who knows, except for a twist of fate or two, I might have followed right along and farmed myself.

But my father had a bit of a mid-life crisis in his 40s. When I was in first grade, he sold the farm and went in with his brother-in-law and a neighbor to buy a Ford Tractor dealership. It was his one big entrepreneurial gamble in life. And for a few years, it looked like it might pay off.

But some lean times for farm prices and some skullduggery by the neighbor-turned-business-partner, and the operation went broke. They had to sell out cheap, and Dad was forced to fall back on his mechanical skills to make a living.

What this meant for me was that I spent most of my formative years in the town rather than on the farm. So, while there were centuries of agrarian instincts bred into me, it didn’t take me long to adapt to indoor plumbing, central heating, and really close next-door neighbors.

And I certainly didn’t miss getting up early to gather eggs, milk the cow, or slop the pigs.

Oh sure, I still hoed beans, bucked bales, and detasseled corn as a hired hand in the summer. But that was a job — not a way of life.

Even if my father had never left the farm, odds are I would have eventually left anyway. That was the demographic trend during the whole last half of the last century. The kids went away to school or to a big city for work, and tended never to move back.

It’s been hard on the farming communities. And I know it was hard on the old folks left behind as their kids fanned out across the country.

When I stop to think about how much different my life has been from the generations before I marvel. I have no explanation for why my entire adult career has been all inside work with no heavy lifting.

My father’s body bore the marks of a hard life in harder times. He was kicked in the head by an ornery horse, and had headaches for the rest of his life. His leg was caught between a hay wagon and a wall, and he walked with a limp. He even had a few scars from surviving what he believed to be a mild case of small pox.

If the American Dream involves working hard and ensuring your children have a better life, then my parents and their generation certainly did their part.