I Sing Not for Glory

I sing not for glory nor for bread,

Nor for the praise of the credentialed clique.

But for hire more valuable instead,

To touch the honest kindred heart I seek.

I sing for lovers when love is green,

When time stops for a solitary kiss.

When light shines anew as with new eyes seen,

I celebrate your fey and fragile bliss.

I sing for the lonely, lovelorn heart,

When light grows cold and aching will not cease,

When your enchanted world falls all apart,

I offer modest salve to give you peace.

I sing for the pilgrim searching soul

Pursuing the heart’s true cause and treasure.

May heaven’s hound, you hasten to your goal,

And propel you to your proper pleasure.

I sing for the wise who see their end,

And, too, for those who have not yet awoke.

For to a common home we all descend,

With common dirt for all our common cloak.

I sing not for money nor for art,

Nor to amuse curators of our trade.

The simple wages of the simple heart

Will satisfy when my accounts are weighed.

©Bobby Ball 2017

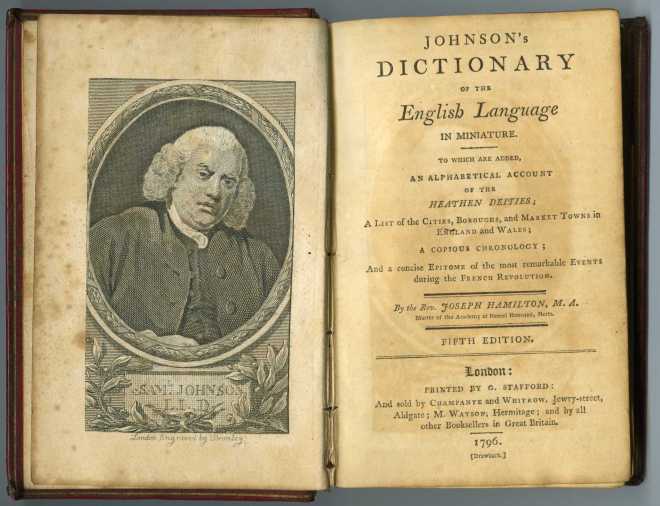

NOTES: Samuel Johnson was a funny guy. If his aphorism is correct, that “no man but a blockhead ever wrote, except for money,” then poets are the biggest blockheads of them all.

A few diligent writers of books and screenplays and advertising copy can manage to make a living scribbling words. But poets need another gig to pay the bills.

Most often, they teach. Gerard Manley Hopkins was a priest and a teacher. Robert Frost famously tried his hand at farming, but he also taught and lectured.

Some poets have conducted quite conventional careers during the day to support their poetry habit at night. Insurance executive Wallace Stevens and physician William Carlos Williams are a couple of well known examples.

Englishman Philip Larkin earned his living as a librarian. American Charles Bukowski was a postal clerk.

Dylan Thomas really couldn’t do much else besides write poems, and so he waged a losing war with poverty until he drank himself to death. He probably would have perished much sooner except for the fact he was able to charm wealthy female admirers into becoming patronesses.

About the only thing I have in common with the aforementioned gentlemen is that while I sometimes commit poetry, I also need another means to make a living.

I started my professional life in the 1970s as an ink-stained wretch of a newspaperman. While chasing deadlines was exhilarating when I was still a young man, there were already storm clouds on the horizon for journalism. Afternoon dailies were going extinct, and cities that had formerly had 2, 3 or more newspapers were seeing them merge or go out of business.

Little did I know that in just a few years, the internet would come along and fatally wound the mainstream media organizations, forcing them to trim their newsrooms and close regional bureaus.

I sensed that there was a disturbing uniformity of political opinion in the newsrooms of my youth. My own political worldview was still evolving, but even back then everybody I worked with seemed to be left-leaning and Reagan-loathing. The lockstep groupthink bothered me.

In my naïve idealism, I thought journalists were supposed to be fiercely objective. I never caucused with any party, and I strove to play my own coverage right down the middle. I’d have coffee with both Democrats and Republicans, and always made sure to pay my own check because I didn’t want to owe anybody anything.

When the owner of one paper tried to pressure me to join the local Rotary Club, I refused because I didn’t want membership to influence my coverage of any organization.

If I had still been a journalist this past year I think my head would have exploded. With news organizations colluding with political campaigns, and sharing debate questions in advance with the favored candidate, it became clear that our creaky old news institutions had jumped the shark.

I would have burned my press card in protest.

I wish I could say I was smart enough to foresee the death of journalism and jump ship intentionally, but it was more random than that. I was about to get married and I needed a job in Minneapolis. The cash-strapped metropolitan dailies weren’t hiring right then, and so I took the first job I could get.

Fortunately I had stumbled my way into direct marketing. That later led me into non-profit fundraising. The bulk of my career since has been helping good causes raise money. Healing the sick, feeding the hungry, caring for widows and orphans, defending the persecuted, visiting those in prison, bringing the good news to those in bondage — that sort of thing.

I began to appreciate what I do a whole lot more when I stopped thinking about it as marketing and started thinking about it as “soul stirring.” When I’m doing it right, I touch the heart to stir people up to good works, and inspire them to be generous.

If you ask me, that’s really just a short step away from poetry. It’s all soul stirring.