In Florida

In Florida the flowers grow

Between the houses, row on row,

While in the trees crows remonstrate

As if to warn, "The time is late!"

And vex the tranquil scene below.

We are the Old. Short days ago

We sold and bought, we mastered fate,

Or so we thought, and now we wait

In Florida.

Next-comers all, be sure you know

The doleful message of the crow.

Be not deceived, there's no debate,

Man does not know his hour nor date.

And so we wait, though flowers grow,

In Florida.

(2024)

The other day, while pondering my complicated feelings about my new home state, I found myself muttering a scrap of what I thought was spontaneous verse: “In Florida the flowers grow, between the houses, row on row.”

Pleased with the sound of this line, I thought, “Hey, I might really have the start of something good here!” But soon I realized it was too good to be true. This snippet sounded much too familiar to be original.

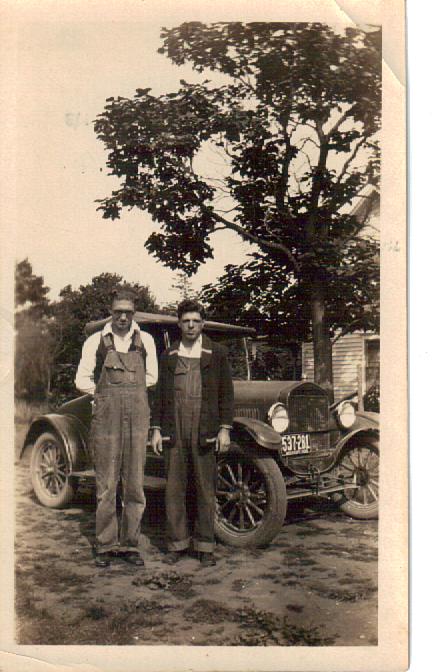

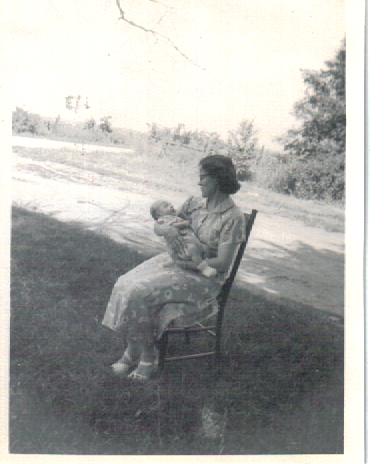

It was, of course, a blatant rip-off of the well known World War I poem, “In Flanders Field,” written by John McCrae, a Canadian soldier who would later die in that conflict. That poem was included in my mother’s precious 1929 edition of “One Hundred and One Famous Poems,” so I must have heard it read aloud many times in my youth. Its words had been buried in my subconscious for decades only to emerge just last week.

Well, darn.

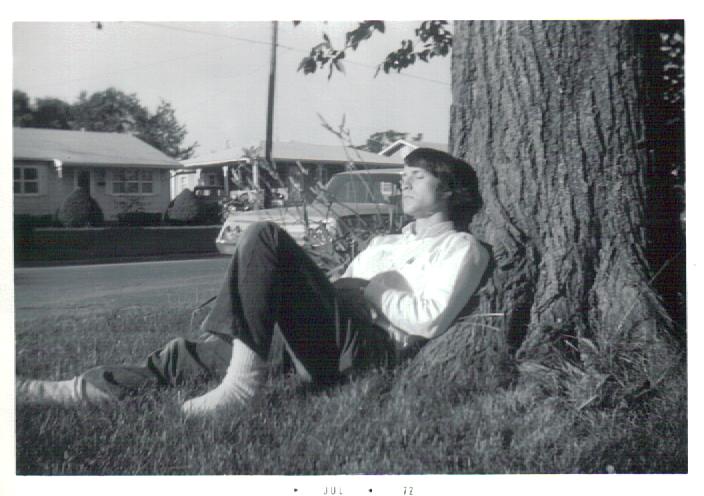

I was hoping that perhaps the muse had returned. I had been in an extended period of writer’s block since moving from Washington State three years ago. In addition to the aggravation of selling a house, packing up, moving across the country, and settling into a new home, I had become the sole caregiver for my wife. A bicycle crash and subsequent spine operation had landed her in a wheelchair. With all that going on I scarcely thought of writing.

But lately, the old itch flared up and I began to sense the need to start putting words on paper again. However, when I realized I was just copying somebody else’s poem, my first inclination was to shelve it and forget it.

Then the thought occurred: Why not take this on as an exercise? I’d rewrite “In Flanders Field” as a way to work through my feelings about our new home. A little poetry therapy, perhaps. And then, maybe, just maybe, other more original ideas would come.

Something about the tone of that poached first line captured the mood … the feelings I was experiencing about this place.

I couldn’t let it go.

Robert Frost once said that writing a poem is having an argument with yourself. I was certainly conflicted about leaving the beautiful Pacific Northwest. But I also love a lot about Florida. You don’t need to bundle up with layers of fleece and rain gear. You never have to scrape ice off your car or shovel the precipitation. The culture still has a decent natural immunity against communist insanity, possibly due to the influx of Cuban refugees who fled when Castro took over in 1959.

That’s all positive. But I still dearly miss our Seattle friends and neighbors, and walks through the changing seasons and cedar-scented hills.

And, once we moved here I began to understand why my wise, late father-in-law, described Florida as “God’s Waiting Room.”

There are sure a lot of old people here! The the most common topics of conversation at social events revolve around health, ailments, and operations. It seemed like we’d just barely settled in and we were already going to funerals of new friends and neighbors.

The whole place is sort of life-sized memento mori.

With all these ambivalent feelings swirling about, I sat down to see what I could lift from McCrae’s poem for my purposes. Somewhere in the process I justified my thievery by likening it to modern recording artists who sample an earlier song and combine it with original material to create something new. Hey, if Snoop Dogg and Beyonce can do it, why can’t I?

But first I had a lot to learn about the poem I was about to rework. I discovered that McCrae wrote it after presiding over the funeral of a fallen friend on May 3, 1915. Legend has it that he was so dissatisfied with his verse that he threw it away only to have it retrieved by his fellow soldiers.

(In a weird bit of synchronicity, I’m pretty sure it was May 3 of this year when I first got the idea for my version. And I, too, initially decided to scrap the idea.)

“In Flanders Field” is a 15-line rondeau with a precise rhyme scheme. This form was popular in medieval and Renaissance French poetry, and later adopted by English poets. I’d never tried to write anything like this before, and took it as a challenge.

I believe my attempt was faithful to the structure of the original, except for the addition of internal rhymes in the last two verses. (A little twist just for fun.)

Time will tell if this warm-up exercise will lead to more inspiration.