I must turn away

All the suffering I see.

I cannot bear it.

I must turn away

All the suffering I see.

I cannot bear it.

Midwinter warm spell,

Evening mist, tree frog calling,

“Cro-cro-cro-crocus!”

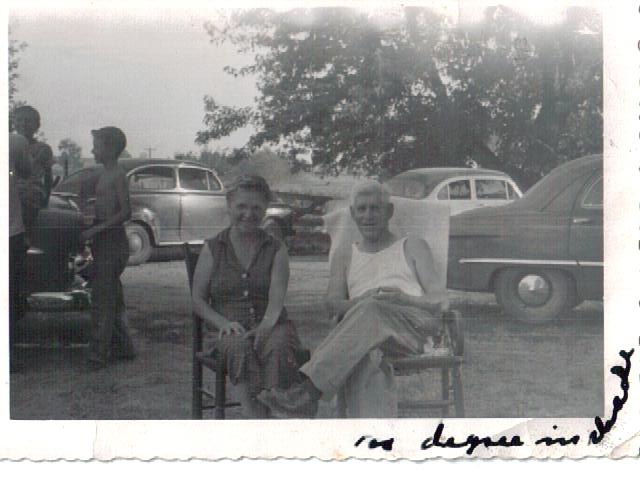

Back in the 1950s on the farm, we didn’t have air conditioning. Shoot, we had just gotten electricity a few years before.

So when the long Missouri summers dragged on and the humidity rose, folks headed outdoors to keep cool. When the nights were really hot, we’d sleep outdoors.

The following poem is about a day pretty much like the one documented in this photo. In fact, the events took place not too many days after this photo was shot.

The Day the Call Came

The day the call came

We had just dished up the ice cream.

A special treat for a Friday farm dinner,

(Not to be confused with supper.)

Mother had made it early that morning in ice cube trays.

“Freezer ice cream,” she called it,

Vanilla, made with Junket tablets to keep it creamy,

Even as it froze.

Not as good as the real, homemade ice cream cranked by hand,

But a whole lot easier.

And America was just starting its long affair with convenience.

The call came over the telephone

Mounted on the farmhouse wall.

With two bells for eyes,

You spoke into its honking, beaklike nose.

The earpiece cradled appropriately

Where the right ear should be,

While a hand crank made a poor excuse

For a drooping left ear.

It was a party line,

So the snoopy widow woman down the road

Knew as soon as we did.

The call came, and the man on the phone

Said Grandpa had just keeled over dead

At the auction over in Poosey.

So, we all got up—Mom, Dad, Big Brother and me,

And climbed into the ’50 Ford sedan

Dad was so proud to own.

The first car he’d ever bought brand new.

By the time we got to the auction –

It was a farm sale, really —

Where the worldly possessions of one farm family

Were being sold off.

One at a time.

By the hypnotically fast-talking auctioneer.

Not as depressing as the foreclosure sales

That were all too common

Just a few years before in the Depression.

This was a voluntary sale,

But a little sad nonetheless.

Some farmer was getting too old to run the place,

And didn’t have kids—or leastwise kids who wanted to farm.

A lot of boys joined the service in those days,

Or headed to Kansas City to find work, and a little excitement,

Rather than stay and try to coax a living

Out of that hilly, rocky dirt.

The man at the auction told us

Grandpa had been standing there in the sun with everybody else.

They were just about to start the bidding on the John Deere hay rake

When he grabbed his chest and fell right over.

Years later, they told me when he was a grown man

Grandpa had gone down to the river,

And been baptized, and filled with the Holy Ghost,

With the evidence of no longer speaking in profane tongues.

For, it was well known Grandpa had been gifted

In the art of colorful language.

“He used to could cuss by note,” was how Mother put it.

But after the washing with water and the Word,

Grandpa was never heard to swear again.

I only knew him as a white-haired old man

With a merry smile, and infinite patience

With Grandma, who required it.

And that was it, really.

Nothing more to say,

Except for the understated condolences

Of the country folk.

Nothing more to do,

Except for my father,

Now lately promoted to the role of the family’s eldest male,

Who assumed the duties and made the necessary arrangements.

Although I didn’t know quite what had happened,

I felt a lurch … as something shifted beneath me …

And I was yanked one more notch forward.

By the time we got back to the house,

The ice cream had long since melted

And now was returning back to solid state,

As it curdled in the September heat.

Hard Times Haiku

I guess we were poor.

Didn’t know what we were missing.

Quite unlike today.

If not for football

Or the women I have loved

I’d hardly know pain.

Pop fixed everything.

Pity that talent wasn’t

hereditary.

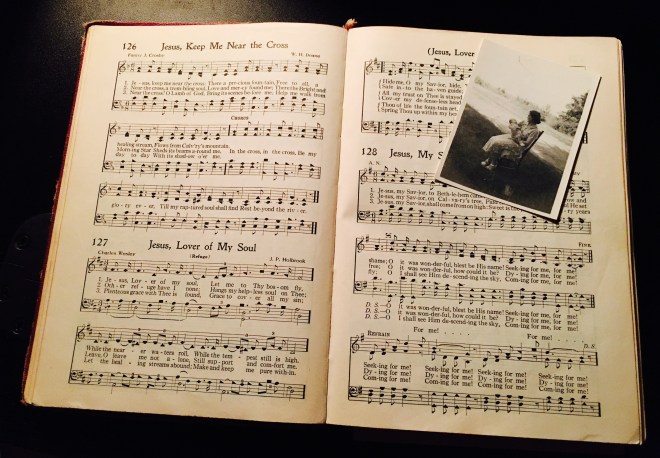

Faith of our forebears.

No organ. No liturgy.

Just Jesus. That’s all.

I had just one job:

“Watch the bacon, don’t burn it.”

Forgive me, I’ve sinned.

Poet and author Mary Karr really stirred the pot last week when she dropped a truth bomb on The New Yorker, and one of the most revered member of the poetry establishment.

On her Facebook page, Mary offered made her friends a hilarious offer:

“A thousand bux to anybody who can explain this dopey Ashbery twaddle. He makes no sense & gets raved about by all the literati. Wins every prize. Nice guy. Waste of time. Snap out of it @NewYorker #theemperorhasnoclothes”

The poet she’s calling out is John Ashbery, who has indeed won every major American poetry honor, including the Pulitzer.

The poem Mary points to is “Dangerous Asylum,” published in The New Yorker’s January 18 edition.

Good for Mary! This poem is an example of the opaque word sausage that gives modern poetry a bad name. I don’t mind working a little bit to understand a poem. But there needs to be a payoff, or I feel cheated. After reading “Dangerous Asylum,” my primary insight is that “well, that’s 3 minutes of my life that I will never get back.”

If the point is that life is absurd, we are all alone, and we will never be able to truly know one another, there are more beautiful, more elegant, more engaging, more efficient, and more effective ways to say it.

Mary’s Facebook post stimulated tons of comments. They ranged from gratitude to her for calling bullshit, to expressions of envy of Ashbery’s success.

One commenter blamed the whole sorry situation on the privilege of “conservative men” with “old ideas.” (Not sure that’s quite it. I’m a pretty conservative man with old ideas, and I don’t care for the poem either.)

My favorite comment: “Cool kid poetry to inspire feelings of cluelessness.”

I do not know the poet’s heart. Mary calls him a “nice guy,” but if his poetry is any indication (and by their works ye shall judge them), he’s saying “I’m smarter and more hip than you. I’m a member of an exclusive inner circle you’ll never be a part of.”

If that’s really what’s going on here, I hate it.

Now, I prefer poems that make connections, that stir up courage and hope, that evoke fear and pity.

I understand there may even be a time and place for poems of alienation, despair and disgust. At least they make me feel something interesting.

In the end, perhaps, the worst reaction a poem can get is not alienation, despair or disgust, but, rather, indifference. If you are writing to make me feel clueless, insignificant, or inferior … I will stop wasting my time on you.

I strive to write poems that would touch my own heart. You can see some examples on this blog.

No way we could know

at this playful reunion,

it would be our last.