Let me not forget

my dual citizenship,

and which one will last.

Notes: Pictured is the First Presbyterian Church of Marshall, Missouri. Known as “The Rock Church,” it is the most beautiful church building in my hometown.

Let me not forget

my dual citizenship,

and which one will last.

Notes: Pictured is the First Presbyterian Church of Marshall, Missouri. Known as “The Rock Church,” it is the most beautiful church building in my hometown.

The old hometown seems

smaller than I remember.

Once, it was magic.

Notes:

For Van Morrison, it was Cyprus Avenue in his hometown of Belfast. The fancy, tree-lined street where the upper class lived. Where a working-class boy went to dream and catch glimpses of aspirational girlfriends.

In my hometown, that street was Eastwood. It was a shady, tree-lined street with what passed for mansions in my little Missouri farm town of Marshall. And there here were even a couple honest-to-Pete mansions among them. Reminders of old money abounded.

To a Johnny-come-lately, working-class kid like myself, it seemed like the coolest place on earth. I lived on the other side of town. Not in the poorest section, but definitely in a different layer. My house was brand new, but it was a plain 1950s ranch house. Utilitarian and homely. Decorated in the finest Late Depression.

At first I didn’t have any friends among the Eastwood society. Unattainable, I thought. But when all of the grade school kids graduated to junior high, we were suddenly thrown together.

I became buddies with an Eastwood kid, Clyde, who, while he didn’t live right on Eastwood, lived close enough — a long block off of it.

His home was a demonstration of exquisite interior decorating, and his family a wonder of graciousness and hospitality. I felt lucky to have such a cool friend.

We played football, we raced slot cars, and talked about our growing interest in girls. I heard Sgt. Pepper’s for the first time in his basement.

When my cat didn’t come home and was eventually found struck to death by a car, I went to Clyde’s to play basketball. I played so furiously that I eventually egged him into our only physical fight.

Because that’s how 12 year old boys grieve.

In those days of flower power and Vietnam, we did find ways to wage a few political protests, and fight against what we saw was hidebound traditions at our high school.

We eventually began to drift our separate ways, spending more time with girls than with our old guy friends.

One evening, late in our high school years, we sat around a campfire out at the park, vaguely aware that our sheltered years in our old hometown were drawing to a close. Our oh-so-enlightened conversation including a one-through-10 ranking of our female classmates.

If I remember, we did try to maintain a sense of irony about it.

The photo atop this little poem is a recent shot of Clyde’s old house.

Hometown Sonnet

The old hometown is aging, as am I,

The once wide streets grow narrow with the years,

As night descends, you all but hear a sigh,

For what once was has gone, and twilight nears.

Now friends and kinsmen number fewer, too,

And memories fade like the painted sign

Proclaiming that the city “Welcomes You!”

Strange how one’s soul and place so intertwine.

Life used to bustle round our stately square

‘Til commerce shifted to the edge of town.

The grand facades are now much worse for wear,

Some landmarks have been torn completely down.

The business of my life took me elsewhere,

Cracks grew in walkways of both man and town.

Notes:

Thomas Wolfe wrote “You Can’t Go Home Again,” but last year I made a couple of trips back to my childhood hometown. My high school class held a reunion, and there was the lingering matter of tidying up my late parents’ estate, which seemed like it would never get resolved.

I thoroughly enjoyed seeing my old classmates, and re-igniting long dormant memories. But, not all my classmates are doing well. Not all of them made it back. Not all are still alive.

The visits led to reflection, and that led to poetry.

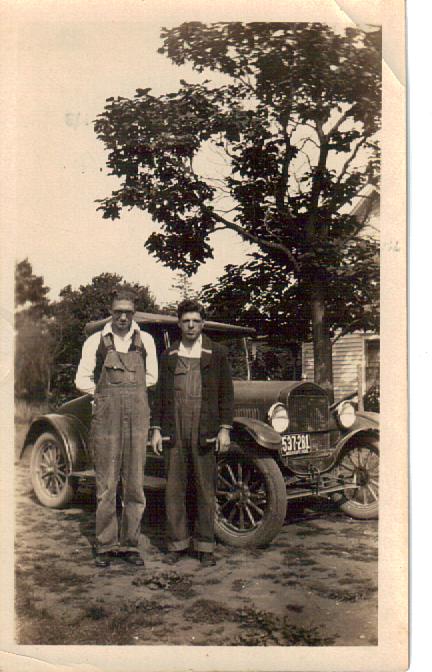

Strategic brothers,

knew the key to a girl’s heart

involved a hot car.

Notes:

My father got in on the ground floor of the automobile revolution. He learned auto mechanics by hanging around the only garage in his small Missouri farm town. He cut his teeth fixing Ford Model Ts, and kept learning from there.

Although he spent years trying to make a living as a farmer, and then as a businessman, he ultimately returned to mechanic work. It was really his true calling.

He could fix things, and make them run. He didn’t buy new cars. He bought old cars in need of work and fixed them up.

When it became clear to him that he was going to be a mechanic for the rest of his life he went out in his back yard, and proceeded to build himself a proper workspace. It looked just like a barn, because that is what he had built before during his days on the farm.

But he built it himself from scratch when he was well past 60 years old. Of course, he used reclaimed lumber scavenged from various tear-downs.

In his later years he ran a mechanic repair business out of his new garage. He was the only mechanic for miles around who would make house calls. The farmers all over Saline County knew that he could be depended on to fix their tractor, hay baler, or corn picker.

The photo at the top of this post shows my father, left, and his brother, Ralph, in front of one of the hot cars of the day.

Like the gentle dove

I neither hate nor judge. But …

like the snake, I watch.

Notes: My childhood friend and schoolmate, John Marquand, takes some of the most beautiful photographs I’ve ever seen. He rises early to get the Colorado morning light, and day after day amazes with remarkable nature photos.

He has become somewhat of a bird whisperer. I’ve never seen great blue heron photos like John’s. But he is not limited to birds. He somehow manages to make even insects look beautiful

John was kind enough to send me this shot of a Eurasian collared dove to illustrate the haiku.

“Liberate the pool!”

We presumed naked meant free.

We didn’t know jack.

Notes

The year: 1970.

Location: A liberal arts college with a reputation for being a little “out there” situated in the upper Midwest.

A delegation of hometown friends make a long journey up to pay a fall break visit to a group of their high school friends who inexplicably all had happened to enroll in the same Liberal Arts College with a Reputation for Being a Little “Out There.”

It’s great to see old friends. Partying ensues. Someone (remembering with fondness the skinny-dipping escapades back home in the bucolic farm ponds and rock quarries of west central Missouri) suggests that a group be formed to go “liberate the pool” on campus.

It seemed like such a good idea at the time.

The word goes forth through the hallways of the dormitories of the liberal arts college with a reputation for being a little out there.

A party is formed, and the pool is “liberated.”

The campus police are called, and the liberators are duly cited for their violations of civility.

I’m not saying who was, and who wasn’t actually there. Or who was a participant, and who was just an observer. Perhaps, you were not available, but you would have gone had you been available. Perhaps, you were horrified at the mere suggestion. Memories get fuzzy when seen through the gauzy veil of so many years.

But, I’ll let the following people explain to their families and descendants just what role they actually played that evening in the notorious Macalester College Skinny-Dipping Affair of 1970:

John Marquand, I’m pretty sure you were not along on that trip. But if you had been, I’m also pretty sure you would have been right there with the other liberators. This is your chance to set the record straight.

Mother’s old Bible,

Worn out from years of long use.

Much like its owner.

Father’s old Bible

held together with duct tape.

Now he’s face to face.

How to explain Dad?

Outstanding in his field, he

lived a simple life.

Well over sixty,

Dad built a barn by himself.

Now it, too, molders.