He Knew the Worth of Tools

He was a man who knew the worth of tools.

How having just the right one for the job

Was worth a lot, but clearly not as much

As knowing what to do with ones you had,

And what to do with tools he surely knew.

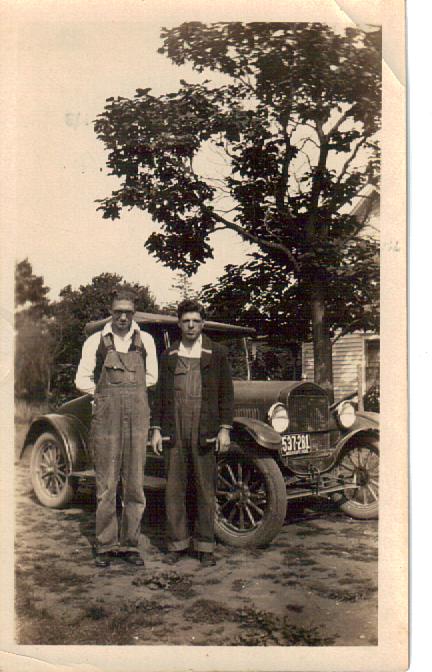

When just a boy on a Missouri farm,

He started hanging round the blacksmith shop

Whenever he could catch a ride to town.

Old Henry Ford’s new-fangled auto car

Had sparked a need for handy fix-it men.

He joined the revolution, then and there,

Brought by the horseless carriage on the land,

And learned mechanics on a Model T.

He mastered use of wrenches and of pliers,

Learned lessons he would use for decades hence.

To make it through the Great Depression’s dearth

He took whatever labor he could find.

He hoed bean rows and stripped bluegrass by hand,

With just the simplest tools to do the job.

His daily wage back then was just a buck,

But any honest work beat none at all.

To earn his daily bread he tilled the soil

Just like his male ancestors all before.

But he saw tools of farming changing too,

With tractors putting horses out of work.

He gambled on a combine harvester

That reaped and threshed and winnowed all at once.

Then hiring out his cutting-edge machine,

He saved enough to buy his own small farm,

And one by one he added to his tools.

In time he sold the farm and moved to town

To try his hand in the commercial world.

Still very much a Ford man in his heart,

He bought a dealership of farm machines—

The boldest speculation of his life.

But business wasn’t really his strong suit,

And when it failed, he carried on with tools.

He built a practice fixing implements —

Hay balers, corn pickers, tractors — all repaired

Right where they’d broken down out in the field.

And farmers round about began to say,

“If Ray can’t make’er run she can’t be fixed.”

When he was well past sixty years of age

He got a crazy notion in his head—

He’d always dreamed of having his own shop—

So he measured out the plan in the back yard.

And there he built the thing all by himself

With salvaged lumber gotten almost free.

Of course, it looked just like a barn.

Because, well, that’s only thing that he’d built before.

But he knew well enough the tools required.

Beneath his hammer, nails sunk into boards

With just two strokes, or maybe three.

His singing handsaw made the sawdust fly.

His level, plane and plumb line kept all true.

Out of a worthless demolition pile

He fashioned form where there was none before.

His barn still stands though many years have passed.

With paint and care could stand for many more.

It needs someone with tools to care again.

And when his wife of more than fifty years

Grew absent minded and began to fail,

He looked in vain for tools to fix her with.

Installed a cook-stove, gas-line, shut-off valve

When she began to start forgetting things,

Like if she’d turned the burners on or off.

Nowhere on all his cluttered workshop shelves

Was there a tool to fix her slipping mind.

The final years he’d visit every day

Ensuring that she ate her rest home meal.

The only tool of any use a spoon.

In time, the spoon was of no use as well.

My work today requires different tools.

I toil in neither soil nor wood nor stone.

Instead of grease my hands are stained with ink.

I polish common syllables to rhyme.

I calibrate my words to find a song,

Fine tuning—like a carburetor—lines,

To make them run not either rich nor lean,

To purr and roar without the gassy fumes,

Obscuring sense and choking with the smoke.

My father’s tools lie idle on the bench.

The workman will not use them anymore.

With all the craftsmanship I can bestow,

I carry on instead with tools I know.

(2019)

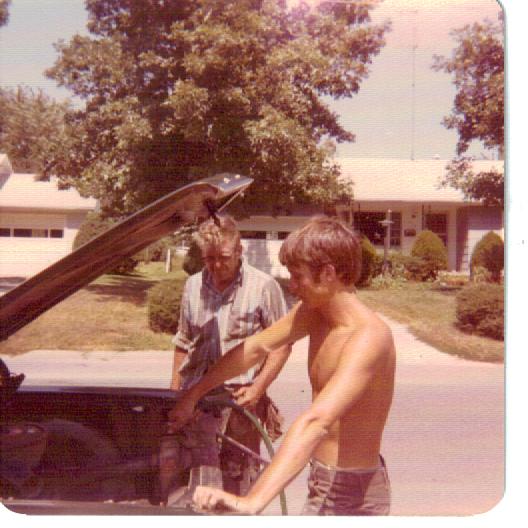

I’m living proof that mechanical aptitude is not necessarily hereditary. You can’t say my Dad didn’t try to teach me automobile repair and maintenance. For years after I had moved out on my own, I dutifully changed my own oil and even greased the suspension as needed.

But my heart never was really in it. As soon as I learned I could pay someone to do that job for me and I could afford it, I gladly hung up my oil filter wrench and drain pan.

If he were still alive, I imagine my Dad would be quietly shaking his head at his spendthrift son paying good money for something I should be doing myself.

Dad didn’t really succeed in turning me into a shade tree mechanic, but he taught me something much more valuable. Lessons about loyalty, service, and love.

When my Mother began her slow descent into dementia, he took care of her at home until his own doctor told him it was killing him and ordered him to have her moved to a nursing home.

Thereafter, every day he was physically able until she died, Dad went to the nursing home to feed his wife her lunch. He did that year after year, long after she could no longer communicate or even recognize him.

These days, when I get a little frazzled taking care of my own wheelchair-bound wife, I remember how my Dad navigated his much, much more daunting challenge.

THE BACKSTORY

If you look up the term “blue collar” in an illustrated dictionary, you might find a picture of my father. Coming of age during the Great Depression, he never finished high school. He had to find a job and bring in some sort of income, pitifully small as it was.

He was raised on a farm, so after he married my Mother, they set out to be dirt farmers like their ancestors before them. It was a tough go, but he kept his family fed and managed to acquire 80 acres of so-so farmland in north Missouri. Along the way, he learned quite a bit about how to keep his farm machines running and in good repair.

After a quarter century of farming, he decided there had to be a better way to earn a living, and he tried to make a go as a partner in a farm implement dealership. But, as the narrative goes in the poem, That didn’t work out.

So he went fell back on his mechanic skills and earned a living keeping machines operating.

His hands were stained with grease and crankcase oil. And neither the Goop grease cutter, nor the green, grainy, Lava soap he used every day got them completely clean.

That’s about as blue collar as you can get.

But he also had a sharp and curious mind. He subscribed to magazines like Popular Science and Popular Mechanics because he wanted to know how things worked. He once told me that he had been pretty good at math in school. He said he wished sometimes that he had been able to continue his studies. He figured he could have been a pretty good engineer.

I knew he thought I was in danger of wasting my college scholarship by majoring in philosophy.

“Be sure to take something practical,” was his main advice to me as I left for school.

Perhaps he indulged my intellectual pursuits because he had a curious hobby for a dirt-farmer-mechanic. He was a student of the Bible and Biblical history. He ordered books by mail and built up a decent library of ancient historians, commentaries, apocryphal literature, alternate translations of scripture.

I still have the bible that he read every day. Fittingly, it is literally held together with duct tape.

By the time he was 80 he had lived to see his two oldest sons die in fluke accidents, and he had been forced to place my mother in a nursing home. He would soon go in for a multiple heart-bypass surgery himself.

I believe that as he increasingly saw the end of his life approaching, he focused more and more on things that really matter. I could do worse.